Can a coal town become a climate leader?

Guest editor Michael Sheldrick tells Western Australia's climate story

I became a climate scientist when I realized how profoundly unfair climate change is. It affects everyone, but not equally. Those who have contributed the least — the poor and marginalized — are hit the hardest.

In turn, climate change acts as a threat multiplier, worsening poverty, hunger, disease, and many other challenges. We need to address climate change precisely because we also want to lift people out of poverty, end hunger, ensure safe housing and clean water, expand access to education and health care, and so much more.

That’s why, this week, I’m delighted to have Michael Sheldrick guest edit this newsletter. Mick is the co-founder of Global Citizen, an international advocacy and education organization working to end extreme poverty worldwide. So far, the group has secured and tracked an amazing $60+ billion in commitments towards ending extreme poverty and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

Michael himself hails from Western Australia and this week he shares its climate story, including the good and not so good news, with us.

Take it away, Mick!

Just as in oil-rich Texas and Alberta, a lot is happening—some good, some not so good—in my home state of Western Australia, a mining powerhouse now seeking to position itself at the frontlines of the energy transition.

Most of Western Australia’s 2.6 million residents live in the state’s southwest, one of the world’s most stunning biodiversity hotspots. For much of the past century, the region’s electricity came largely from coal, supplied by the town of Collie, a town of just over 7,500 residents located about a 2.5-hour drive from Perth, the state’s capital (and my hometown). Today, Collie is fast becoming a best practice example of how to phase out coal without abandoning workers or communities.

As renewable energy became cheaper and pressure for climate action grew, Western Australia’s government announced in 2022 that all its remaining state-owned coal plants—all located in Collie—would shut down by 2029. Since then, nearly $700 million Australian dollars has been committed to help the town build new jobs and income streams by attracting new industries to the area like battery recycling and green steel and support the retraining of workers. In April, Collie completed construction on one of the country's largest battery projects—an AU$1.6 billion investment designed to help keep the grid stable as coal phases out. The town will also soon host the region's first battery maintenance hub, creating at least 50 new jobs.

Western Australia is also home to Fortescue Metals, one of the world’s largest iron ore producers and a major force in Australia’s mining sector. Its founder, Andrew Forrest, has set one of the most ambitious goals in global mining: to eliminate fossil fuels entirely from Fortescue’s Australian operations by 2030. No offsets. Just a complete switch to clean power, electric trucks, and battery-powered trains. He’s backing that promise with more than $6 billion USD in investment to make it happen.

As for Collie, other projects are in the works. Early ventures in green magnesium and graphite processing are moving forward. Local businesses, including tourism operators, shops, cafes, and restaurants, are also expanding, providing young people with a reason to stay in town rather than leave to find work.

The town’s main street reflects this progress. Restored buildings have won heritage awards. State-funded mountain bike trails are drawing outdoor visitors. Overall, tourism is up nearly 75 percent. As the local MP put it: “I used to joke that I knew everyone in town—now, on Sundays, I can walk down the street and not recognise a single face.” For both Collie and Western Australia as a whole, this is a great development!

Western Australia is already one of the world’s top LNG exporters—that’s natural gas cooled into liquid form so it can be shipped globally. If it were a country, Western Australia would be the third-largest LNG exporter in the world, behind the U.S. and Qatar.

In May, the Australian Government approved a 40-year extension for the North West Shelf, Western Australia’s largest gas project, operated by energy company Woodside. The decision triggered debate across the country and beyond.

Pacific Island leaders, First Nations representatives, environmental groups, and hundreds of protestors outside Woodside’s Perth offices called the extension a “carbon bomb,” warning it could lock in 4.3 billion tonnes of carbon pollution through to 2070—equivalent to nearly a decade of Australia’s annual emissions, or more than the total emissions of many mid-sized countries in a single year. They argue it would make it harder for the country to meet its climate targets. Western Australia is currently the only Australian state where emissions are still rising, while the country as a whole has cut emissions by more than a quarter since 2005.

Proponents argue that natural gas remains a vital transition fuel, especially for countries in Asia where coal use is still high and many coal plants are relatively new and harder to replace. They note that Australian gas could help displace coal while green alternatives like wind, solar, and battery storage continue to scale up [a nearly identical argument to what’s being made in Canada as well! -KH]. The International Energy Agency has previously lent support to this view, but only in scenarios with very strict methane controls and clear timelines.

Debates about the role of gas in a decarbonizing world are not new, but the timing of this decision is notable. It comes just as Australia competes with Turkey to host COP31, the 2026 UN climate negotiations. The backlash could shape how Australia’s climate commitments are judged on the world stage.

We often think climate action belongs on big stages: summits, parliaments, and press conferences. And yes, national governments do set important targets that can rally society at large. But whether those targets succeed or fall apart often comes down to what happens at the community level, because that’s where policies are felt, tested, and either embraced or resisted.

At its core, Collie’s story is about building trust in a transition plan and ensuring it has real community buy-in. It’s worked so far, not because it was handed down from above, but because it was shaped through conversation and partnership between unlikely allies.

For years, tensions ran high between coal workers and environmental activists. Unions fought to protect jobs. Activists protested outside power stations. Both sides saw the other as part of the problem.

But that began to change when a union official told me: “If we wanted ideas about the future, we figured maybe it made sense to talk to the people who were obsessed with it. … It was the first time many of the coal workers had even spoken to an environmentalist before.”

And to their surprise, once these conversations started, they found common ground. The workers weren’t anti-climate. They just didn’t want to leave their hometowns to find work.

Instead of arguing, they started co-creating solutions. They knew Western Australia was relying more on renewables, and that new systems, like battery storage, would be essential. So they asked: “Why not house the batteries in Collie?” With a skilled workforce and strong infrastructure, the town had something to offer.

They invited the government to join their table, not the other way around, and asked for regular, honest updates. When the government eventually returned to announce the coal closures (along with a sweep of transition investments), it was met with applause rather than protests.

Progress came from persistence, honesty, deep listening, and a willingness to work across divides. That’s a lesson every community can use: whether the issue is coal, farming, or flood risk. Who will be affected? What do they care about? And what would it take to make them part of the solution?

The good news is that there are growing networks that support this kind of community organizing. In the U.S., Climate Changemakers organizes “hours of action” for everyday people—often with no background in climate or politics—to spark conversations with neighbors, coworkers, or friends about what change could look like in their own communities.

If you’re looking to get involved in their work, follow @theclimatevote on Instagram and visit Climate Changemakers for weekly events and resources. After all, to quote Eleanor Roosevelt, “the way to begin is to begin.”

👋 Katharine, here!

Thank you, Mick, for sharing these great stories with us!

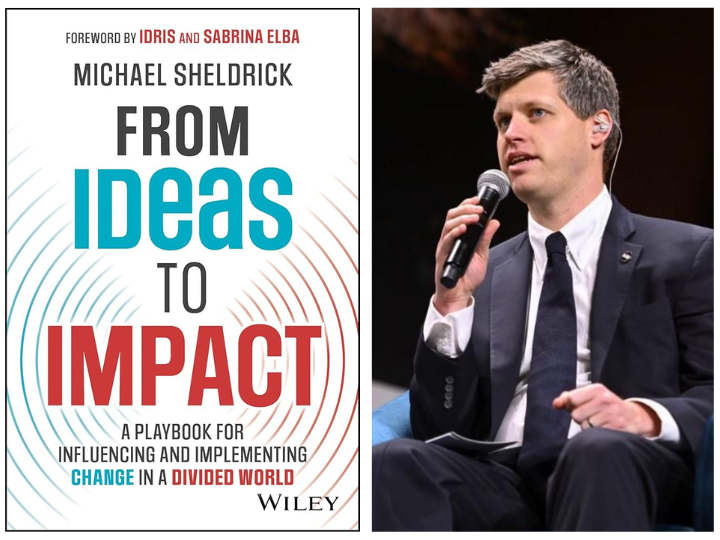

I recently finished Mick’s book, From Ideas to Impact: A Playbook for Influencing and Implementing Change in a Divided World. It tells the story of Collie in more detail, as well as giving many other examples of how individuals have catalyzed changes that are shaping the world.

I was encouraged and challenged by what he shared in the book, and wanted to tell you: if you feel frustrated with what you’ve been able to accomplish in making the world a better place, and you want to move from good intentions to lasting impact, this is the book you should read. You will come away inspired and full of ideas of how you can make a difference!

I loved reading this piece, Katharine. Thanks for writing it!

COP31 is mentioned in this positive essay and as I write there is currently a scramble to host the high-profile event in South Australia's capital so I thought I would take a look at one item on its original agenda and see how it was fairing - Loss and Damage.

Loss and Damage is basically where developed countries financially assist undeveloped countries so that they can make the transition to lower emissions.

Although mentioned on the first agenda it wasn’t discussed until COP6, and at COP9 it was ‘looked at,' and then at COP11 they agreed to establish a fund.

At COP12 a plan was adopted but they couldn’t agree on the funding and neither could they at subsequent meetings until ....

COP17 where it was agreed that the fund would distribute $100B pa.

But there were no pledges so nothing happened until ten years later at COP27 where $700 million was pledged. A fraction of what was needed.

At COP28 the text for the fund was finalised - the meeting's only achievement except for the wording on a non-binding agreement to ‘begin to move away’ from fossil fuels.

And we think COP31 is going to be any different?

My apologies to climate scientists who gave presentations at COP over many years in a futile effort to warn us about the threat that climate change poses.